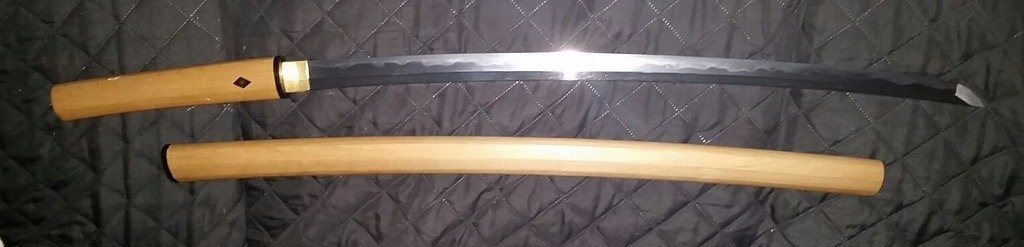

They can bend easily!! Cutting poorly can easily result in a badly bent blade. Tameshigiri ruins a lot of blades and people recommend not using a valuable historical antique blade for doing tameshigiri because it can greatly devalue it, plus need more polishing and restoration. You need to have clean technique to not torque the blade in the cut when you meet resistance. Spine and edge have to be in the same plane before contacting the target, during contact with the target and after clearing the target.

Tons of myths and rumors about Japanese blades, including that they never break, never bend, cut through machine gun barrels, cut a floating flower stem in the river, drop silk on it and it cuts with no movement, cuts through trees, etc. They are very strong, but can be damaged just like any other sword. They can be extremely tough due to the different steels ie hard and soft steel just like if you blue back a knife blade.

Different periods of Japanese used different styles of swords, too. Some periods favored longer, more curved blades, others wanted shorter, straighter blades. Some were more ornate, others were simpler. During periods of frequent war, the blades werent as beautiful (active hamons and interesting hada patterns) , bit may have been stronger since they were built for war, not show and had to be made quickly.