KentuckyFisherman

Well-Known Member

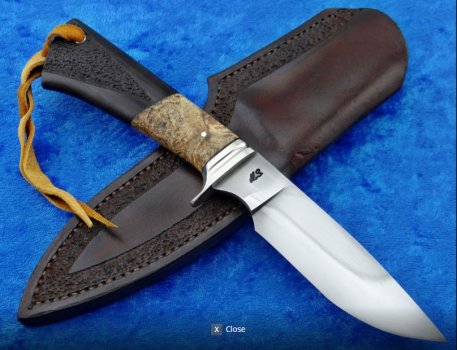

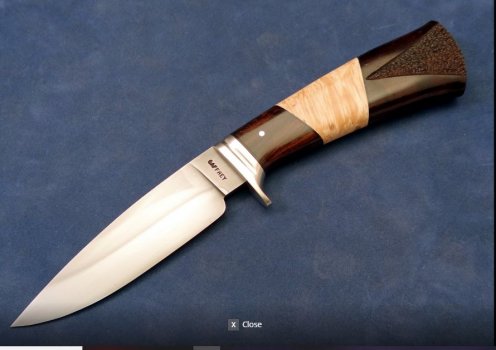

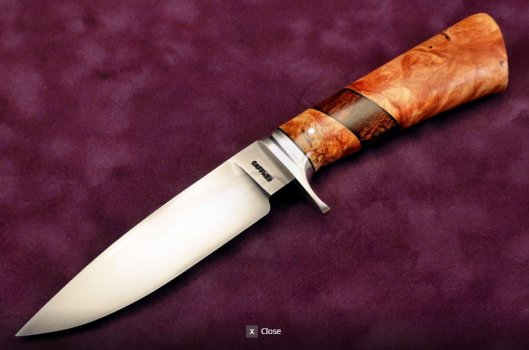

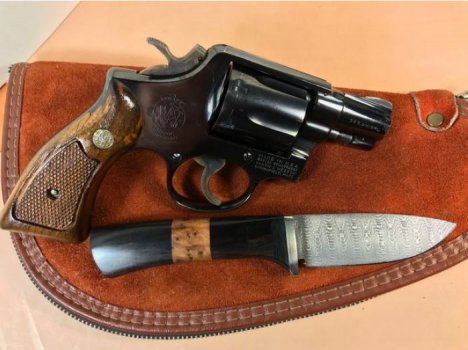

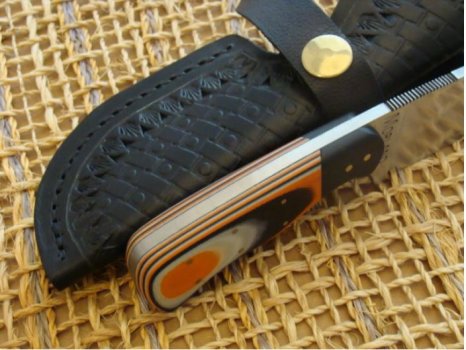

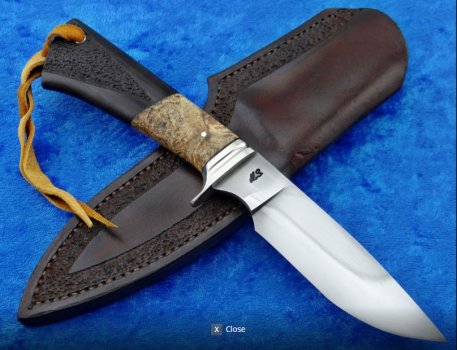

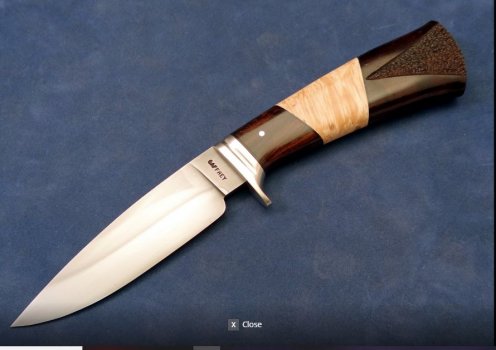

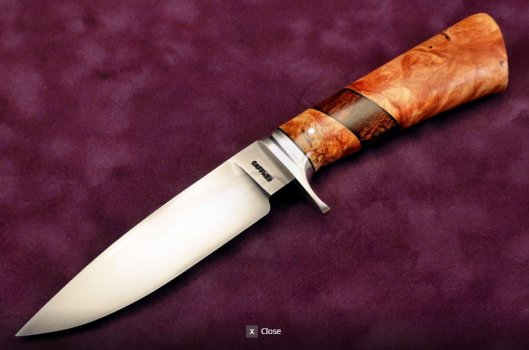

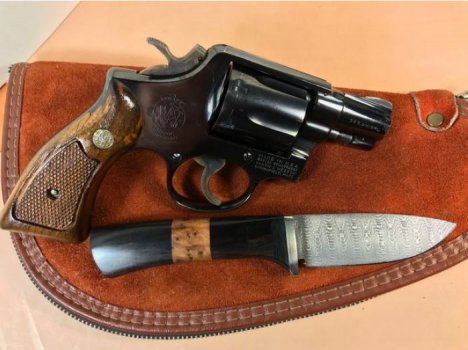

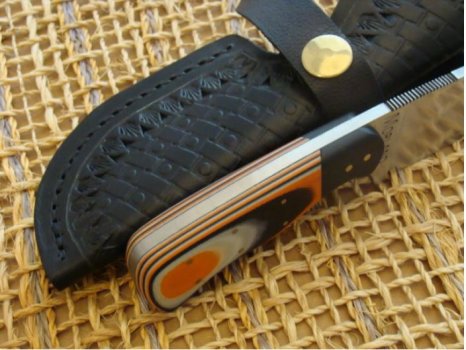

I'm still very much a newbie, only adding scales to purchased blades at this point, and I've just bought the tools to begin making sheaths. So much to learn. I'm hoping someone here has done a step-by-step or a video showing how some of the first-class makers on KDF get such precise, beautiful joinery (right word? wrong word?) in their handles. I don't have a woodworking background and I don't have a clue how to begin getting fitment like is shown in these scales. Sometimes it's a scale that's fit to an angled bolster. Sometimes it's a scale made of two materials and perfectly joined at an angle. I'm not asking for anyone's trade secret technique, and maybe there are several ways to do this, but I'm just fascinated by it and want to learn. Here are some examples, and I hope some of you can point me to a thread or maybe a YouTube video. Thanks in advance. Knives are by Caffrey, Opaul and Morland. I didn't ask their permission, but I'm lifting these up as excellent examples of what I'm trying to describe, so I hope that's OK.